- Exhibitions

- By Day & by Night: Paris in the Belle Époque

By Day & by Night: Paris in the Belle Époque

The belle époque, a French expression meaning “beautiful era,” refers to the interwar years between 1871 and 1914, when Paris was at the forefront of urban development and cultural innovation. During this time, Parisians witnessed the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the ascendancy of the Montmartre district as an epicenter for art and entertainment and the brightening of their metropolis under the glow of electric light. From the nostalgic perspective of the 20th century, this four-decade period of progress and prosperity was a golden age of spectacle and joie de vivre.

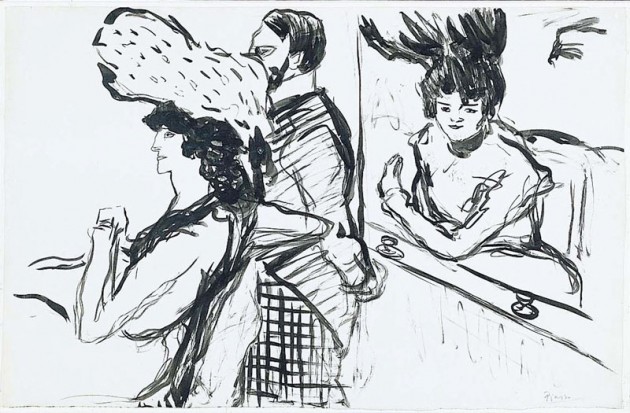

For artists living through the epoch, however, the less triumphant details of daily life were often the ones that inspired creative expression. Armand Guillaumin painted plumes of factory smoke as they mingled with pale, puffy clouds. Photographer Eugène Atget captured the eclectic assortment of lampshades peddled by a traveling salesman, as well as the quasi-comical uniformity of a crowd of strangers viewing a solar eclipse. Portraying the bustling metropolis encouraged informality and a new kind of attention to fleeting moments. In Women Ironing, Edgar Degas seeks to evoke a glimpse through the door of a steamy laundry (though the painting itself may have taken over 10 years to complete), while Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Cirque Fernando, Rider on a White Horse (1887–88) dramatizes the sensation of movement by depicting a bareback circus performer as she whips by on her mount. All of these images exploit the startling dichotomy between physical proximity and emotional distance that was closely associated with urban existence in fin-de-siècle France. SHOW MORE

To convey the immediacy of what they observed, many artists rejected the formalities of oil painting, preferring loose, sketch-like handling, abrupt compositional cropping and oblique points of view to situate the spectator within the scene. Camille Pissarro’s lively Poultry Market at Pontoise (1882) positions the viewer as a potential customer or fellow farmer, squeezing past a woman in a red head scarf with a basket full of fresh eggs. Pierre Bonnard employs a similar strategy in his portfolio of color lithographs Some Aspects of Life in Paris (1899); in House in the Courtyard, the artist aligns the margins of his composition with the frame of a window, obliging us to peer past the open shutters to peruse a neighbor across the way. These protocinematic views of modern life present Paris as an endless source of pictures, if we only take the opportunity to look.

The graphic arts—and color lithography in particular—enjoyed something of a renaissance in the belle époque, and painters like Bonnard turned to printmaking as a newly compelling medium, one that invited bold aesthetic experimentation while broadening the potential market for avant-garde art. The Norton Simon is fortunate to own three of the most groundbreaking suites of lithographs produced in this period: in addition to Some Aspects of Life in Paris, these include Édouard Vuillard’s Landscapes and Interiors (1899) and Toulouse-Lautrec’s Elles (1896). Each is an exercise in extending the pictorial experience beyond a single frame, even while the portfolio as a whole refuses to cohere into a comprehensive narrative. Alongside these limited-edition initiatives, Bonnard and Toulouse-Lautrec used lithography to make large-scale, dynamically designed posters that were plastered throughout the city to advertise products ranging from champagne and lamp oil to literary journals and famous nightclub entertainers. By Day & by Night includes six iconic posters, generously lent by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, to demonstrate the pervasiveness of visual art in a city increasingly associated with the ubiquity of printed images.

By Day & by Night: Paris in the Belle Époque surveys the rich range of artistic responses to life in the French capital through the diverse and interrelated media in which its practitioners worked. Taken together, these paintings, drawings, prints and photographs reveal that artists participated in the inventive spirit of the age by interpreting the everyday as something extraordinary. SHOW LESS