Goya's Don Pedro, Duque de Osuna, on Loan from The Frick Collection, New York

The Museum is pleased to welcome the splendid Don Pedro, Duque de Osuna, by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828). This special loan is the third in a biennial exchange series with The Frick Collection in New York that was initiated in 2009—a program that has also brought to Pasadena other revered treasures from that esteemed institution. Osuna’s portrait joins the three other Goya paintings and one drawing in the Norton Simon Museum’s permanent collections. In celebration of this rare loan, the Museum also presents a small installation of a subset of the assemblage of over 1,450 etchings and lithographs by Goya that Norton Simon amassed during his lifetime.

Mr. Simon’s fascination with Goya is understandable in the context of his own collection and the artist’s position in the timeline of the history of art. Goya’s formative style was greatly guided by his Spanish forebears and others, especially Velázquez, Tiepolo, Mengs and Corrado Giaquinto, as well as his teacher and brother-in-law, Francisco Bayeu. In turn, this long-lived artist undeniably influenced 19th-century French artists, from the Romantics to the Realists, such as Courbet and Manet, who were clearly drawn to the master’s freedom of style as well as his satirical commentary on society, religion and politics. Given his placement in this chronology and the fact that he was born at midcentury, Goya is often called the “last Old Master”; the first 20 years of his career were largely devoted to tapestry design and religious fresco work. However, his politics, social conscience, brushwork and shift toward portrait and genre painting by the mid-1780s place him soundly in the 19th-century arena, and it is not without reason that he has also been seen in this context as the “first modern artist.” His repertoire of portraits started relatively late in his artistic career, as he was nearing his 40th year. The commission for the Frick portrait came about a decade into this part of his oeuvre, in the mid-1790s, as his renown as a portrait painter attracted the attention of royalty and aristocrats alike, including the ilustrado Don Pedro Téllez-Girón, 9th Duque de Osuna (1755–1807), who was one of Goya’s most important clients and loyal patrons.

Both the duke and his wife, María Josefa Pimentel, 15th Countess of Benavente (1752–1834), continued the tradition upheld by their aristocratic families as major patrons of the arts, as supporters of humanist exploration and as generous hosts of salons at their palace in Madrid and their French-inspired country estate known as “El Capricho de la Alameda de Osuna.” Perhaps the countess-duchess surpassed even the duke in her enthusiasm for intellectual stimulation and culture and in her taste for all things French. Her gatherings of liberal writers, botanists, artists, scientists and bullfighters vied with those of her closest female counterpart, the renowned 13th Duchess of Alba, who was also a pivotal presence in Goya’s life.

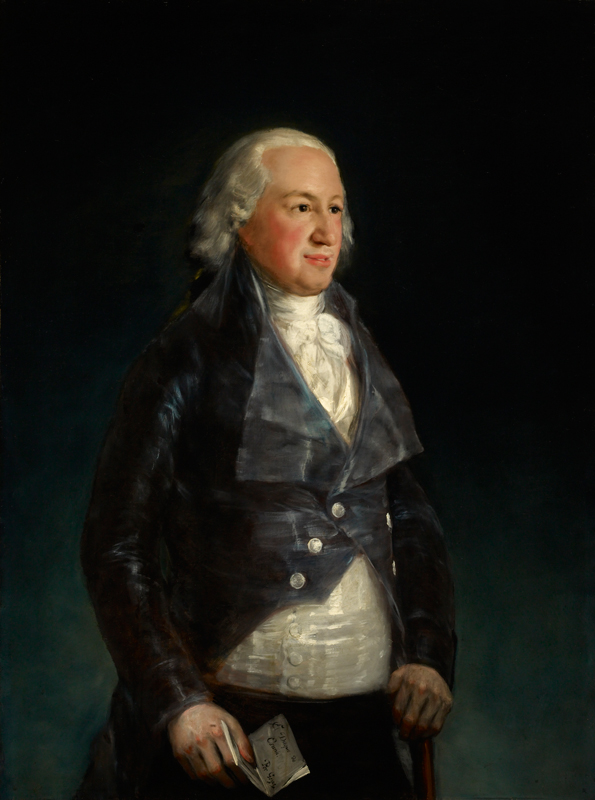

Over the course of 15 years, the duke and his wife provided Goya with commissions for nearly 30 paintings, including decorative panels for their home and portraits of themselves and their family. They were also avid collectors of his prints. The Frick portrait was the third known likeness of the duke to be executed by Goya, and most scholars date it to the mid-1790s. Unlike the first portraits of the duke and his wife (1783–85), which were very tightly painted in the academic tradition, the Frick’s portrait is surprisingly informal. The duke is shown standing, in three-quarter profile against a plain, dark background, with long hair and wearing a subdued silk tailcoat, the cut and color of which are in a combination of the more reserved French and British styles that were in vogue. Except for the flourish of his jabot, the silver buttons and the sheen of his waistcoat, there is very little hint of extravagance, and there is a noted absence of medals and honorific decorations that Osuna was known to have received by 1795, after serving in several campaigns against the French. He stands in a relaxed pose, his balance checked jauntily by a walking stick, and his other hand grasps a partially unfolded letter, dedicated to him from the artist himself: El Duque de Osuna. Por Goya. The letter reminds us of Goya’s own prodigious practice of letter writing and especially of a missive that he wrote to the duchess of Osuna, reminding her that he had not yet been paid for work he had produced for them. In the Frick painting, the duke’s countenance is pleasant, his dark eyes have a bemused, familiar regard, and he appears to be smiling or about to speak. Had the latter been the case, his words would have most likely gone unheard by the painter, as Goya had lost his hearing in 1793 after a serious illness.

This grand, mysterious portrait remained with the Osuna family until the profligate reign of the 12th duke, who was forced to sell most of the ducal collection in 1896. The painting was later in the possession of the financier/philanthropist J. Pierpont Morgan, and it finally came to reside in the Frick Collection in 1943, where it joined three other dramatic late paintings by Goya that were purchased in 1914 by Henry Clay Frick.

Featured Media